The Hidden Foundation That Powers Every Query You Run

When you write SELECT * FROM Users WHERE Id = 42, you probably think about tables, rows, and indexes.

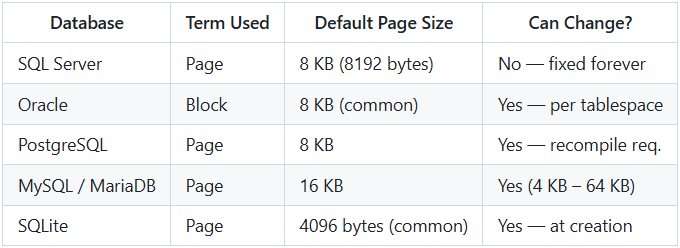

But long before your row reaches the execution engine, the database engine has already performed a crucial step: it read one or more 8 KB (or 16 KB) chunks from disk called pages (or blocks).

These pages are the real physical building blocks of every major relational database. Understanding them is the difference between guessing why a query is slow and knowing exactly why.

What Exactly Is a Page (or Block)?

A page is the smallest unit of data that a database reads from or writes to disk in a single I/O operation.

Think of it like this:

- You ask for one sentence from a book.

- The librarian doesn’t hand you just that sentence.

- She hands you the entire page the sentence lives on.

That’s exactly how databases work.

Anatomy of a Typical Data Page (SQL Server Example)

An 8 KB SQL Server data page looks like this in memory/disk:

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Page Header 96 bytes |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Data Rows variable |

| (actual table records) |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Free Space variable |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Row Offset Array 2–4 bytes per row |

| (pointers to start of each row, at end of page) |

+--------------------------------------------------+

Total = exactly 8192 bytes

The 96-byte header contains:

- Page number (Page PID)

- Previous/next page pointers (for heap or clustered index)

- Page type (data, index, LOB, IAM, etc.)

- Free space available

- Checksum (if enabled)

- LSN (Log Sequence Number)

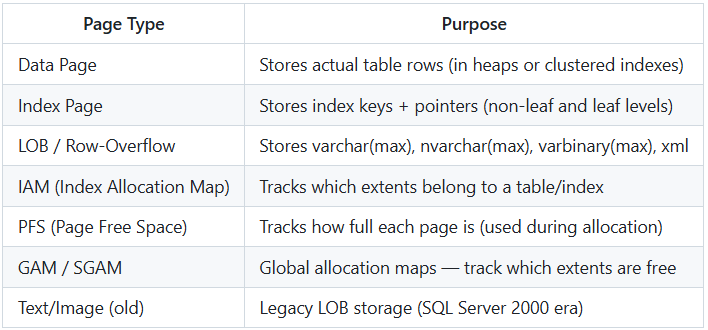

Different Types of Pages

Not all pages store regular table rows.

Why Page Size Directly Affects Your Database Design

-

Maximum Row Size

SQL Server: ~8,060 bytes per row

→ Because a row must fit on a single data page (minus header and offset array).

→ Anything larger → automatically moved to LOB/row-overflow pages.

-

Wide Tables Force More Pages → More I/O

A table with 10-byte rows can store ~800 rows per page.

A table with 7,000-byte rows stores only 1 row per page → 800× more I/O.

-

Index Depth

Smaller page size = more levels in B-tree = slower seeks.

That’s one reason MySQL InnoDB moved from 8 KB → 16 KB default.

The Dreaded Page Split

Imagine a page that is 98% full. You insert or update a row that no longer fits.

What happens?

- Database allocates a brand-new page.

- Roughly half the rows move to the new page.

- Both pages are now ~50% full.

- Physical order on disk may now be fragmented.

Result:

- Wasted space (internal fragmentation)

- Slower range scans (external fragmentation)

- Heavy write amplification

This is why DBAs obsess over fillfactor and rebuild/reorganize indexes.

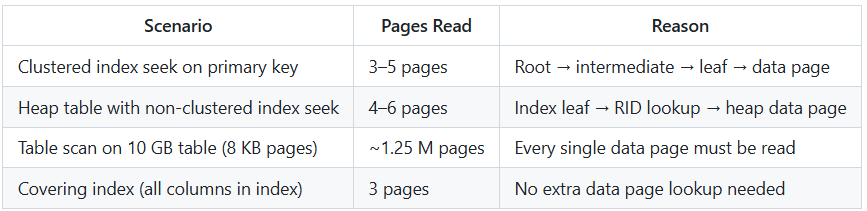

Real-World Performance Examples

How to See Pages in Action

SQL Server

-- See what is actually on a page (undocumented but safe)

DBCC TRACEON(3604); -- redirect output to SSMS

DBCC PAGE ('YourDatabase', 1, 12345, 3); -- file 1, page 12345, style 3

PostgreSQL

-- Install and use pageinspect extension

CREATE EXTENSION pageinspect;

SELECT * FROM page_header(get_raw_page('users', 0));

Oracle

-- Dump a block

ALTER SYSTEM DUMP DATAFILE 4 BLOCK 42;

MySQL InnoDB

-- Use innodb_ruby or Percona’s tools

innodb_space -f data/ibdata1 page-dump 100

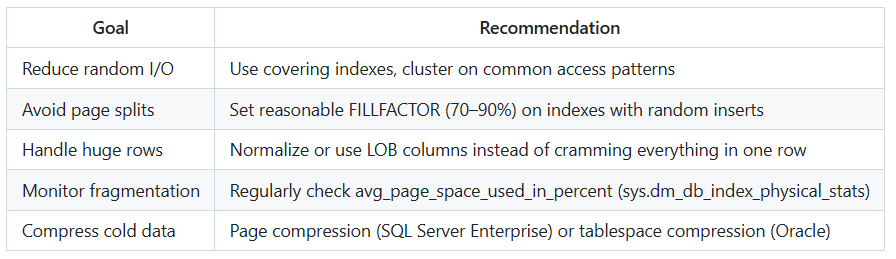

Best Practice Checklist Based on Page Knowledge